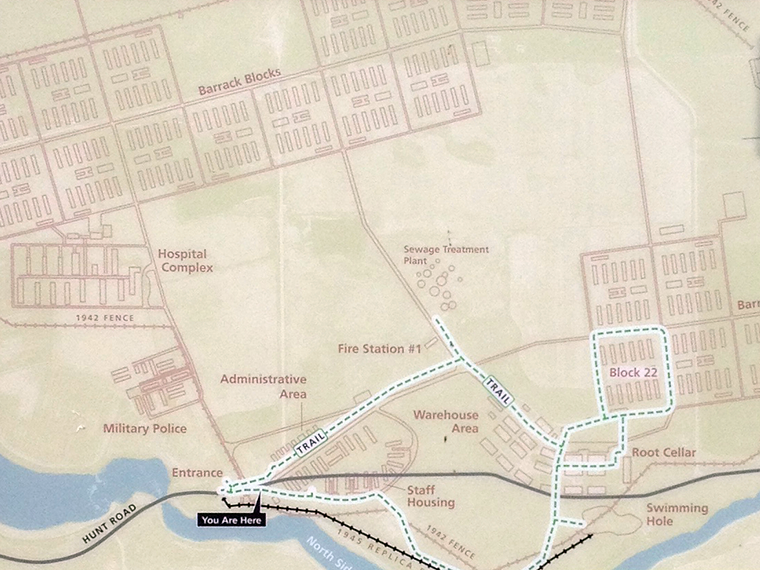

Seventy-five years ago, on February 19, 1942, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 allowing for the creation of Japanese-American internment camps during World War II. The Executive Order would not be suspended until over two years later, in December 1944, when internees were released to rebuild their families, businesses, lives, and sense of dignity. Although the camps were shut down by 1946, the EO was not rescinded until 1976 (by President Gerald Ford) and the federal government did not formally acknowledge the injustice until the Civil Liberties Act was passed in 1988, offering an apology and a small level of reparations. I visited the Minidoka National Historic Site a few years ago (my gallery, here) and was struck by how much of it has been erased in comparison to the map of the camp, seen above.

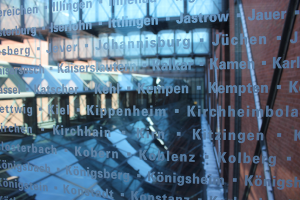

Although I’m sure I was told about the existence of Japanese-American internment camps (and prisoner of war camps on American soil) at some point during my youth, it wasn’t until I began to study the US Holocaust Memorial Museum in college that I truly began to understand all the different things a “camp” could be, most of which included some level of community erased. Researching James Ingo Freed’s museum design was part of my quest to understand memorials, including memorials to tragedies, disasters, and fallen architecture. I was not disappointed by my first visit to the museum just two years ago (image above). The architecture is evocatively integrated into the narrative presented.

The perspective I had gained, however, was rewritten when I took a side trip to Poland during a graduate school trip to the Czech Republic. My friend Carolyn and I boarded an overnight train from Prague to Krakow, and from there a bus to Auschwitz. I often call myself the historian with the worst memory, but much of that trip to Auschwitz is firmly seated in my mind. It upended my understanding of the personal stories of the holocaust as learned through Anne Frank, Schindler’s List, and the research I had completed years earlier. Most poignantly, I recall a singing and skipping school group leaving the facility after their tour. Their revelry should have been jarringly out of place in such a sacred spot and yet it seemed almost appropriate, as though they were reasserting the vitality that should have been there all along. The bright sunny day made capturing various viewsheds nearly impossible, perhaps reinforcing my need to remember what I was witnessing through my heart and mind rather than the camera lens.

America has a long history of “camps” as well. And, although the Japanese-American internment camps did not ultimately have the same genocidal consequences as Auschwitz and camps like it, internment camps for American Indians certainly aimed for that outcome. And the enslavement and lynching of people of African heritage essentially sought a similar result. As I strive for better understanding of the institutional bigotry within which we live, I continue to be struck by how many of my fellow Americans are oblivious to the reverberations these government-sanctioned actions have had, including the continued marginalization of anyone considered “other.”

And so here we are again. This week’s #ADayWithoutImmigrants is just one recent action carried out in opposition to executive orders and unbelievably privileged government attempts to marginalize Americans. There are no camps (yet) and nobody has uttered the word genocide, but it is a real attempt to undermine the foundations upon which this country was founded. As a historian, am I forced to “stand by helplessly while everyone else repeats [history],” as a recently recirculated Tom Toro comic suggests?

No. Not in the least. In my own way I will continue to resist attempts to extinguish Lady Liberty’s lamp. You might not know it by reading my blog, nor will you necessarily understand by following me on social media. But this historian is not just watching. She is trying to figure out how to change her world—our world—for the better. I certainly hope you are doing the same.

New Colossus (1883)

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

MOTHER OF EXILES. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

—Emma Lazarus (1849–1887)